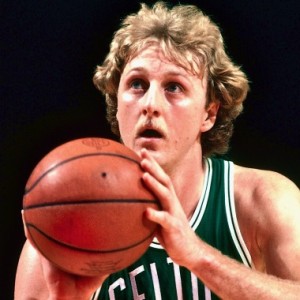

Larry’s skills in the sport of basketball are what separated him from the competitors. Outside of the possession of sports skills, what other ways can we train athletes to separate themselves?

What separates athletes from their competitors is the word itself, separation — gaining it on the offensive side, or taking it away on the defensive side (There are exceptions of course, one being the contest of offensive linemen and defensive linemen in football where the inverse is true). Speed, strength, and power are great ways to create separation in sports. However, speed, strength, and power all have genetic ceilings.

“Although speed can be improved, it is inaccurate to suggest that everyone has the capacity to become a sprint champion,” explained the NSCA’s Ian Jeffreys. This is not to imply those aforementioned characteristics of athleticism should not be sought out to improve/maximize in the realm of athletic performance training. But one should consider other ways for the athletic “have-nots” to gain ground, or an advantage on the athletic “haves.”

Developing skills within the sport is the obvious course of action, and the most effective — Larry Bird sure didn’t become one of the greatest basketball players ever because of his speed, strength, and power. In the realm of athletic performance training however, body control is a key attribute that will allow an athlete to create separation, even if their level of speed, strength, and power is not significant among competitors.

The term body control is not universally defined with regards to its athletic application. It also has no tangible measurement like speed, strength, and power does. For the purpose of identifying how to train it, let’s define it as the ability to coordinate the use of force according to the demand of the sport. For example, a basketball player driving to the rim must apply force to get by the defender, but they must also coordinate that force in order to maintain the skill and control to finish the basket without causing a charge.

Again, speed, strength, and power are all crucial for an athlete to develop, and it’s an essential part of any quality performance training program. An athlete being able to control their speed, strength, and power though is what will increase their chances of winning the separation battle with their opponent. Along with speed, strength, and power, body control needs to be a focal point in the performance training of an athlete.

A car with bad brakes is a lot like an athlete with poor body control, a disaster waiting to happen.

Think about a Ferrari with shoddy brakes. That Ferrari will have no trouble gaining separation from another car going straight ahead for an extended distance. The issue with the brakes becomes a problem once change of direction comes into play. Because of the Ferrari’s poor brakes, the driver has to brace themself sooner for the change of direction, allowing for the other cars to gain ground. Having poor body control is similar to a car having shoddy brakes. An athlete may be faster than competitors, but if they need to brace themselves for change of direction sooner because of poor body control, then they limit their performance.

In linear sports like sprinting and swimming, body control is not much of an issue. But in sports like basketball, football, and hockey, where change of direction constantly occurs, body control is a huge factor.

Not having blazing speed, but having command of his speed is what allowed Rice to dominate football for two decades.

Jerry Rice, the NFL Network’s choice for “Greatest Player Ever,” saw two receivers selected in front of him in the 1985 NFL Draft. One of the concerns about Rice was that his 4.6 40-yard dash was not fast enough to be an elite receiver in the league. What Rice possessed that played a big role in his record-breaking career was impeccable body control. It allowed him to stop, start, speed up, and slow down on cue. It allowed him to be a dynamic route-runner. Rice would separate from defensive backs in the 80’s and 90’s like Liz Taylor would separate from spouses.

Along with speed, utilizing strength and power in athletics also requires body control. The degree of the application of strength and power in sports, like speed, is situational. The more force an athlete exerts, the more balance and control become compromised. Offensive linemen need to use the right amount of strength against defensive linemen without losing balance. Think back to the aforementioned example of a basketball player exploding to get to the rim from the perimeter, and that they must also maintain control so they do not commit an offensive foul.

In a lot of ways, better body control can help those slower and weaker (“have-nots”) athletes equalize, or even outperform those who are faster and stronger (“haves”).

Body Control Training

How do we train it? We do it by improving the athlete’s ability to accelerate and decelerate. Acceleration and deceleration is exactly what occurs in the majority of sports, so it’s important we train the athletes in those sports to be adept with it.

Three effective ways to train body control in the realm of performance training are developing the posterior chain, the use of plyometrics, and ensuring stability of the body.

Developing the posterior chain, and strengthening the hamstrings will improve the body’s ability to decelerate following an explosive movement like a sprint, push, or jump.

Plyometrics demand the athlete to accelerate in order to engage in an explosive jump, and decelerate on the descent of the jump in order to execute a soft, controlled landing. Plyometrics are a simple, and practical implementation in performance training for replicating the demands of sports that require change of direction.

Developing stability of the body allows for more precise execution of athletic movements. Stability ensures proper posture and alignment of the body, and a strong core to facilitate range of motion.

Body control is not the ‘end all, be all’ to becoming great at a sport. If that was the case, Olympic gymnasts would be able to compete in any sport at any level. What body control does though, is it accentuates speed, strength, and power in athletics. Training those attributes should always be a focus, but to ignore the need for an athlete to develop the body control of those attributes is doing that athlete a disservice.